In her acceptance speech after being awarded a laureate by the Nordic Committee for Human Rights, the author appeals to policymakers in India to resist and reject the Western models of child protection.

Goodafternoon and greetings from India to all of you!

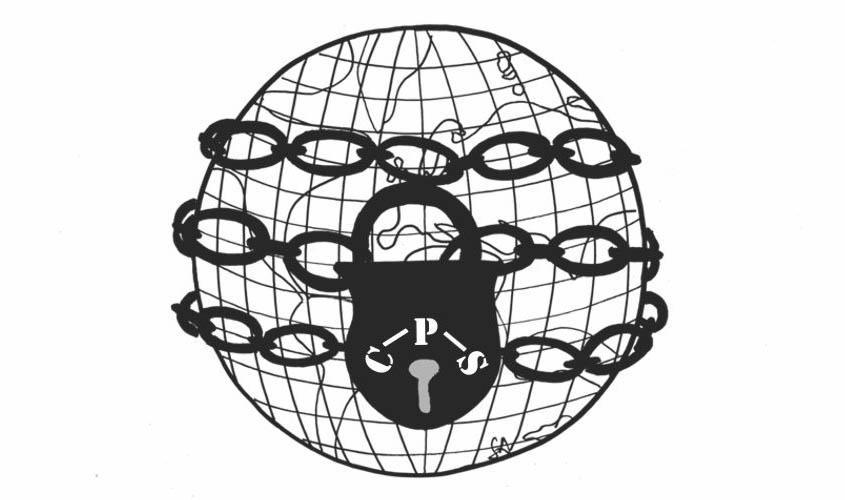

Let me begin by saying how touched and honoured I am to receive this award from the Nordic Committee for Human Rights. Looking at the list of my fellow laureates, past and present, I am doubly honoured. These are people who have accomplished a lot, and sometimes at great cost, in exposing the wrongful snatching of children by the state in different parts of the world. For me to find this endorsement of my work among you abroad, to have won your trust and your friendship is very gratifying. There are only a handful of us in each country fighting for justice against child protection services or “CPS” as we call them. But I believe that if we work together, then we will eventually succeed in persuading the public, our governments, and international organisations that CPS in its present form has failed.

This is important not just in your countries, but also in my part of the world. Here in India, UNICEF, Save the Children and billionaire philanthropist organisations have been lobbying our governments and public influencers to adopt this same mistaken model of child protection.If CPS can go so wrong, become so corrupt and power-mad in your countries despite your celebrated systems of public accountability, you can imagine the havoc they would wreck in mine. It must not happen, and you must help us prevent it. You must help us in India save our 440 million children, and their mostly simple, humble parents, the majority of whom live in very difficult circumstances already, and whose only joy is their children. You must help us stop CPS from poisoning their lives here.

In a way you’re already helping. Your work, exposing the problems with CPS in your countries, helps us persuade people here in India to reject this system. If you win against CPS in your countries, then we win against CPS here. So in a very real sense we are all in this together, and we should join hands internationally in fighting CPS.

We all agree that child abuse is wrong and should be punished. But due process has to be followed. Without due process, you are at the mercy of state authorities—and that is what makes the difference between a democratic and an undemocratic system. Due process and a healthy skepticism of all government authority are the distinguishing features of a free society. But all skepticism seems to vanish when you start asking people about child protection agencies. What is the reason for this blind spot in the public eye? I think that they simply do not believe that child protection agencies are violating basic human rights; that child protection investigations and trials are unfair and biased and children are being taken from their parents without good reason.

So what can we do about this? I believe we have to do more to show the public that child removals are taking place for reasons falling far short of any common understanding of abuse. That children are being taken even where there is no physical or sexual abuse, and no issue of drug or alcohol addiction. We have to show, that judges are ordering removals even when they say, in so many words, that the children are loved by their parents and have not faced any abuse or abandonment by them.

To convince people, we need the information about non-physical/sexual abuse removals to come from the government itself. I mean removals such as those for “risk of future emotional harm”, “attachment disorder” and poverty-related assessments of neglect. Let governments come clean on child protection cases that do not involve physical or sexual abuse, or parental drug or alcohol addiction.

We have some clues from the official data that many, if not most, child protection cases, do not involve physical or sexual abuse. In Norway, Bufdir’s latest report says that “parents’ lack of care abilities” and “high degree of conflict in the home” are the two most frequent reasons for children and the young to come into the child welfare system. But “parental lack of care abilities” can mean anything. The official data has to give us more details to be meaningful. If none of these cases of “parental care abilities” cases involve abuse, then the government needs to say so.

We are told that CPS intervenes only in the most serious cases, but I have seen figures from Statistics Norway in the past, where the annual percentage of physical abuse and sexual abuse was as low as 1.8% and 0.6% of the new cases. If the same pattern exists for care orders, and not just for the initiation of cases, then we are looking at a situation of widespread removals for non-physical or sexual-abuse reasons. This places the whole child protection enterprise on an entirely different footing to what governments are telling the public—that this is reserved for extreme cases of abuse.

So we need to mobilise a demand in Norway for meaningful official statistics about the reasons for placing children in care. For the statistics to be meaningful, and this applies to all countries (not just Norway), there should be a separate heading for the number of cases where there is no allegation of sexual or physical abuse. There should be a separate heading for the number of cases involving drug or alcohol addiction. There should be clear figures of the cases of separations that are done on purely psychological assessments like attachment disorder or emotional harm. In the physical abuse category, the figures should state how many cases involved spanking or other mild forms of physical intervention, and how many involved serious violence. These facts will speak for themselves, and they must come from the mouth of the government.

In England, there are no official numbers on the children taken for “risk of future emotional harm” or “parents’ failure to co-operate with social workers”. This is very misleading, because we are seeing care orders where these are the given reasons for placing children in care. If you look at the numbers in England for children subject to a “child protection plan” [the step prior to taking a child into care], physical abuse cases are at 6% and falling, and sexual abuse cases are at 4% and falling, while emotional abuse and neglect cases are at 30-40% and rising for each year since 2012. This shows a much greater number of emotional abuse than physical or sexual abuse cases. If in England, the pattern for “looked after” children is same as that for children subject to a “child protection plan”, then again we are looking at a situation, where the drastic action of permanently confiscating children from their families is not taking place in situations that the public generally assumes it does—such as incest, violence or abandonment—but for the much more questionable categories of emotional abuse and neglect.

We see a similar situation in the USA. US official figures for foster care show a relatively small number of cases, under the heads of sexual and physical abuse—sexual abuse is at 4% and physical abuse at 12% of cases. The vast majority of cases—61%—are reported in the category of neglect. So again, we are looking at a huge number of cases, that do not involve the kind

In England, the data for looked after children is not helpful as it clubs all abuse and neglect cases together under a common head called “abuse or neglect”. But abuse can mean a range of things, and so can neglect. For the data to be meaningful, abuse and neglect cases have to be separated and then they have to have sub-categorised, so that we can drill down and see what types of behaviors, incidents and home conditions, are being classified by the authorities as abuse

and neglect.

What these gaps in the official statistics show us is that the governments in all these countries which are so stubbornly defending their child protection systems, themselves don’t really know what CPS is up to. They don’t know about the mushrooming emotional abuse and risk of emotional harm cases. They don’t know about the sliding threshold for labeling something as physical abuse or neglect. And they don’t know about neglect allegations arising from parental poverty. In Norway, where the system is heavily reliant on psychological assessments and the theory of attachment disorder, how can the government claim to have effective oversight over Barnevernet when it does not even have Attachment Disorder as a heading in its own statistics about child protection cases?

So I propose we prioritise mobilising opinion on this issue and demand that authorities give clear data on emotional harm and neglect, broken down into meaningful sub-categories as I have discussed earlier.

I will stop here as time is limited. Thank you again to the Nordic Committee for Human Rights for their award. I will cherish this and salute you from India. To victims of CPS: all my love and solidarity. You are not alone. We bear witness to your suffering. We stand by you to the bitter end. To my beloved fellow activists, I wish us all good fight! One day victory will be ours. Thank you.

Suranya Aiyar is a New Delhi-based lawyer and mother. The Global Child Rights and Wrong series is run in collaboration with her website www.saveyourchildren.in, critiquing the role of governments and NGOs in childpolicy